New feature - The Book Awards Shop

Tuesday, March 31, 2009 by 1morechapter

I hope you'll like this new feature -- happy shopping!

Tuesday, March 31, 2009 by 1morechapter

Posted in:

Announcements

|

0

comments

|

|

![]()

Thursday, March 26, 2009 by Becky

Spiegelman, Art. 1986. Maus I: A Survivor's Tale: My Father Bleeds History.

This is a true-must-read of a book, well, a graphic novel to be exact. But still, must-read at all accounts. I loved the format of this one. No, not just the graphicness of it. But the framework of the story. How this novel is just as much about a father-son relationship--in all its complications--as it is about Jewishness, about the Holocaust. I also love the exploration of the psychology of it. So often with "Holocaust" books the issue of long-term effects, of psychological and emotional trauma that persists through the decades following such a horrific event, doesn't come up. It's a non-issue. Often memoirs are about a specific period of time. Liberation comes from either the Americans and the Russians. And voila. Horror over. But life isn't that easy.

In this first volume, we meet Artie, an artist, and his father, Vladek, a Holocaust survivor who is grumbling his way through a second marriage to a fellow-survivor, Mala. (Artie's mother, Anja, committed suicide in the late 1960s.) Artie seeks out his father in this volume wanting to hear his story, his past. Seeking answers to questions not only about his father, but his mother as well. Questions about the Nazis, the war, the Holocaust, how these two survived despite the odds. We, as readers, follow two stories, the contemporary setting where a son is asking some hard questions of his father and getting inspired to write about them in graphic novel form, and the historical setting--1930s and 1940s--where we meet his parents and learn their stories and backgrounds.

His father isn't in the best of health, and their relationship is strained. The book addresses the question of if parents ever really understand their children and/or if children can ever truly understand their parents. Can stressful tensions--ongoing issues and conflicts--ever be resolved peacefully? The drama is just as much about healing as it is the Nazis. And I think that is one of the reasons it's so powerful, so resonating. These characters--represented as mice in the novel--feel authentic. They're flawed but lovable. Their stories matter. (By the way, the Nazis are cats. The Polish are pigs. The French are frogs.)

The story is continued in Maus II.

Spiegelman, Art. 1991. Maus II: A Survivor's Tale: And Here My Troubles Began.

If Maus I was great, Maus II is even greater. If you thought the first one was heart-felt and moving, wait until you get to this one. Everything is more intense. The sorrows and griefs are even deeper; the actions even more troubling. For here we get to the heart of the story. The darkest place of all. Artie's father and mother have been captured by the Nazis and sent to a concentration camp. (In this graphic novel, the name is "Mauschwitz" instead of Auschwitz.) In the contemporary story line, we see that Artie's father isn't doing well; in fact, it becomes obvious, that he's dying. This complicates things tenfold. More guilt. More anger. More frustration. Even in fine health, Artie had a difficult time getting along with his father. Now, when his father perhaps needs him more than ever, he's crankier and grouchier and meaner than ever. Life isn't easy. Never easy. This is a complex novel--graphic novel--with heart and soul. Highly recommended.

Posted in:

Becky's Book Reviews,

Pulitzer Prize

|

0

comments

|

|

![]()

Monday, March 23, 2009 by Anonymous

Sunshine is the nickname of Rae Seddon. When she was younger her mother left her father and she has been raised to be her mother's daughter. This becomes more apparent as we learn her father was a sorcerer from the famous Blaize family. Sunshine works in a bakery where she is famous for making her delicious cinnanmon rolls among other pastries and deserts. Everything changes though one day when she takes a drive up to the lake and doesn't hear the vampires coming (well you don't do you).

Sunshine is the nickname of Rae Seddon. When she was younger her mother left her father and she has been raised to be her mother's daughter. This becomes more apparent as we learn her father was a sorcerer from the famous Blaize family. Sunshine works in a bakery where she is famous for making her delicious cinnanmon rolls among other pastries and deserts. Everything changes though one day when she takes a drive up to the lake and doesn't hear the vampires coming (well you don't do you).

Posted in:

mythopoeic award,

Rhinoa

|

1 comments

|

|

![]()

Tuesday, March 17, 2009 by Becky

Dick, Philip K. 1962. The Man in the High Castle. 272 pages.

For a week Mr. R. Childan had been anxiously watching the mail.

What can I say about this one? Really. An alternative reality is created, a reality in which the Axis powers won World War II. The United States? Not so united. They've been divided--some being more occupied than others--between Germany and Japan. Life isn't all bad--well, unless you happen to be Jewish or black. For this reason, it is better to be on the Japanese side of the border. (Don't even ask what the Germans did to Africa.) This nightmarish reality is all too real for the handful of characters the reader meets. (Yes, a few of the characters are Jewish.)

Decisions. Decisions. Decisions. This book is all about choices--ethical and moral questions that these characters have to answer. It isn't easy to be the person you want to be, should be. Life is too complex to be simplified into wrong and right...or so it appears. Some decisions change your life forever. Some change who you are. Some hasten the inevitable...death itself. How much of yourself would you be willing to sacrifice to be "safe" in this nightmare-of-a-world?

One of the fascinating aspects of this one is how the novel revolves around a book or two. Specifically, the novel revolves around another novel and its author. A science-fiction novel that in itself is an alternate reality. A novel imagining what life would be like if the Allies had won the war. This novel is by Hawthorne Abendsen. It's called The Grasshopper Lies Heavy. And this novel weaves its way into the stories of the many characters and narrators. As you can imagine, this novel isn't all that popular with the powers-that-be. It's outlawed on the German-occupied side of the country. But that doesn't stop people from reading it. Giving this novel power. If anything, it makes it all that more popular.

This one is definitely interesting! It's a bit more philosophical and ideas-oriented than action-packed. But I enjoyed reading it.

Plot summary (from the publisher?)

It's America in 1962. Slavery is legal once again. The few Jews who still survive hide under assumed names. In San Francisco, the I Ching is as common as the Yellow Pages. All because some 20 years earlier the United States lost a war--and is now occupied jointly by Nazi Germany and Japan.

This harrowing, Hugo Award-winning novel is the work that established Philip K. Dick as an innovator in science fiction while breaking the barrier between science fiction and the serious novel of ideas. In it Dick offers a haunting vision of history as a nightmare from which it may just be possible to awake.

Posted in:

Becky's Book Reviews,

Hugo Award

|

0

comments

|

|

![]()

by Laura

Schindler's Ark

Schindler's Ark )

)

Posted in:

Booker Prize,

Laura,

Review

|

0

comments

|

|

![]()

Monday, March 16, 2009 by Anonymous

The 2006 Booker Prize winner set in the foothills of the Himalayas and part of the time in New York. We follow Sai the orphaned gradaughter of the judge she lives with. He treated his wife terribly and disowned his daughter, but his one love is dog Mutt who he completely spoils. Living with them also is Cook whose son Biju has been sent to New York to find a better life.

The 2006 Booker Prize winner set in the foothills of the Himalayas and part of the time in New York. We follow Sai the orphaned gradaughter of the judge she lives with. He treated his wife terribly and disowned his daughter, but his one love is dog Mutt who he completely spoils. Living with them also is Cook whose son Biju has been sent to New York to find a better life.

Posted in:

Booker Prize,

Rhinoa

|

0

comments

|

|

![]()

Saturday, March 14, 2009 by Becky

Steinbeck, John. 1961. The Winter of Our Discontent. 304 pages.

When the fair gold morning of April stirred Mary Hawley awake, she turned over to her husband and saw him, little fingers pulling a frog mouth at her.

"You're silly," she said. "Ethan, you've got your comical genius."

"Oh say, Miss Mousie, will you marry me?"

"Did you wake up silly?"

"The year's at the day. The day's at the morn."

"I guess you did. Do you remember it's Good Friday?"

He said hollowly, "The dirty Romans are forming up for Calvary."

Despite it's rather odd opening, The Winter Of Our Discontent held my interest. It is the story of a man, Ethan Hawley, and his family, his good wife, Mary, his son, Allan, his daughter, Ellen. It's a story of the conflict between ambition and honesty. Ethan has always found himself to be a good man, a just man, an honest man. A man who plays by the rules.

Despite it's rather odd opening, The Winter Of Our Discontent held my interest. It is the story of a man, Ethan Hawley, and his family, his good wife, Mary, his son, Allan, his daughter, Ellen. It's a story of the conflict between ambition and honesty. Ethan has always found himself to be a good man, a just man, an honest man. A man who plays by the rules. But Ethan is noticing the world around him. Noticing that businessmen--including his banking friends--are more concerned with money, with making a profit, than by doing right by their customers. Dollar signs have got them mesmerized. They don't see their family, their friends, their neighbors, their acquaintances. They've lived in town their whole life--know practically everyone--yet when it comes down to it--money comes first and foremost over being kind and compassionate and concerned. Everyone is looking out for their selves. Everyone is greedy. Everyone is selfish. If it's good for you--financially beneficial--then it's right for you no matter who else gets hurt. So Ethan begins to contemplate joining them. If everyone does business this way, lives this way, then maybe it's time he joins them, enters the so-called real world; maybe if he does then his wife will have something to be proud of. She wishes--the children wish as well--for more money. And her friend, Margie, says its in the cards. Her tarot card readings have shown that Ethan is about to strike it rich. With this "prophecy" Ethan decides to go for it...step by step. But will this descent into the "real world" be his undoing?

But Ethan is noticing the world around him. Noticing that businessmen--including his banking friends--are more concerned with money, with making a profit, than by doing right by their customers. Dollar signs have got them mesmerized. They don't see their family, their friends, their neighbors, their acquaintances. They've lived in town their whole life--know practically everyone--yet when it comes down to it--money comes first and foremost over being kind and compassionate and concerned. Everyone is looking out for their selves. Everyone is greedy. Everyone is selfish. If it's good for you--financially beneficial--then it's right for you no matter who else gets hurt. So Ethan begins to contemplate joining them. If everyone does business this way, lives this way, then maybe it's time he joins them, enters the so-called real world; maybe if he does then his wife will have something to be proud of. She wishes--the children wish as well--for more money. And her friend, Margie, says its in the cards. Her tarot card readings have shown that Ethan is about to strike it rich. With this "prophecy" Ethan decides to go for it...step by step. But will this descent into the "real world" be his undoing?  Will his ambition lead to a happily ever after ending? Will his actions--some quite cutthroat when you think about it--be something he can be proud of at the end of the day?

Will his ambition lead to a happily ever after ending? Will his actions--some quite cutthroat when you think about it--be something he can be proud of at the end of the day?A day, a livelong day, is not one thing but many. It changes not only in growing light toward zenith and decline again, but in texture and mood, in tone and meaning, warped by a thousand factors of season, of heat or cold, of still or multi winds, torqued by odors, tastes, and the fabrics of ice or grass, of bud or leaf or black-drawn naked limbs. And as a day changes so do its subjects...(514)

"Way I look at it, it doesn't matter about believing. I don't believe in extrasensory perception, or lightning or the hydrogen bomb, or even violets or schools of fish--but I know they exist. I don't believe in ghosts but I've seen them." (560)

A man who tells secrets or stories must think of who is hearing or reading, for a story has as many versions as it has readers. Everyone takes what he wants or can from it and thus changes it to his measure. Some pick out parts and reject the rest, some strain the story through their mesh of prejudice, some paint it with their own delight. A story must have some points of contact with the reader to make him feel at home in it. Only then can he accept wonders. (569)

What a frightening thing is the human, a mass of gauges and dials and registers, and we can read only a few and those perhaps not accurately. (576)

Sometimes I wish I knew the nature of night thoughts. They're close kin to dreams. Sometimes I can direct them, and other times they take their head and come rushing over me like strong, unmanaged horses. (587)

It's hard to know how simple or complicated a man is. When you become too sure, you're usually wrong. (634)

I wonder about people who say they haven't time to think. For myself, I can double think. I find that weighing vegetables, passing the time of day with customers, fighting or loving Mary, coping with the children--none of these prevents a second and continuing layer of thinking, wondering, conjecturing. Surely this must be true of everyone. Maybe not having time to think is not having the wish to think. (676)

Posted in:

Becky's Book Reviews,

Nobel Prize

|

0

comments

|

|

![]()

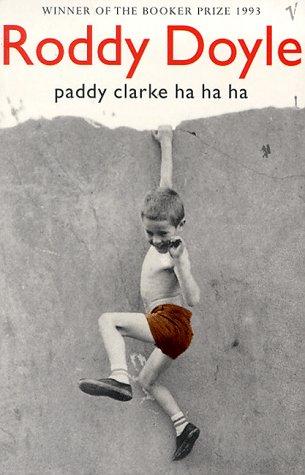

Tuesday, March 3, 2009 by J

Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha is the story of a ten-year-old Irish boy in 1968. The book is told in Paddy's voice, and Roddy Doyle captures the confusion and attempts to make sense of the world that go along with being 10, suppositions and extrapolations that children make. Paddy on death and religion:

When Indians died - Red ones - they went to the happy hunting ground. Vikings went to Valhalla when they died or they got killed. We went to heaven, unless we went to hell. You went to hell if you had a mortal sin on your soul when you died, even if you were on your way to confession when the lorry hit you. Before you got into heaven you usually had to go to Purgatory for a bit, to get rid of the sins on your soul, usually for a few million years. Purgatory was like hell but it didn't go on forever.

It was about a million years for every venial sin, depending on the sin and if you'd done it before and promised that you wouldn't do it again. Telling lies to your parents, cursing, taking the Lord's name in vain - they were all a million years.

-Jesus

-A million

-Jesus

-Two million

-Jesus

-Three million

-Jesus

Robbing stuff out of shops was worse: magazines were more serious than sweets. Four million years for Football Monthly, two million for Goal and Football Weekly. If you made a good confession right before you died you didn't have to go to Purgatory at all; you went straight up to heaven.

But it took two to tango. He must have had his reasons. Sometimes Da didn't need reasons; he had his mood already. But not all the time. Usually he was fair, and he listened when we were in trouble. He listened to me more than Sinbad. There must have been a reason why he hated Ma. There must have been something wrong with her, at least one thing. I couldn't see it. I wanted to. I wanted to understand. I wanted to be on both sides. He was my da.

Posted in:

Booker Prize,

J

|

0

comments

|

|

![]()

Sunday, March 1, 2009 by 1morechapter

Powered by... Mister Linky's Magical Widgets.

Posted in:

Linkys

|

0

comments

|

|

![]()

Copyright 2007 | All Rights Reserved.

MistyLook made free by Web hosting Bluebook. Port to Blogger Templates by Blogcrowds